The History of Social Security

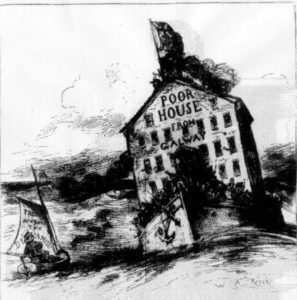

What we know as Social Security today actually had its origins in 17th century England’s poor laws, which provided care of the less fortunate. The Pilgrims brought these laws to the New World in the form of poorhouses or monetary relief. In 1862, disabled veterans of the Civil war, their widows and orphans received government pensions and later, old age became a criterion. Company pensions began in 1882.

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, most people lived on farms, and if people aged or became disabled, their families took care of them. Once people moved to cities, often away from family, if they lost their jobs or became disabled or were unable to work, they had no help. Some states passed social assistance legislation, but once the Great Depression hit, Franklin D. Roosevelt realized most programs, which were dependent on the government, charities or private citizens, were inadequate. In 1934, he created a committee and tasked them to come up with a plan for creating economic security. There was much debate in Congress, but on August 14, 1935, he signed the Social Security Act into law, which included:

- An old-age pension program

- Employer-funded unemployment insurance

- Financial assistance for widows with children

- Financial assistance for the disabled

- Health insurance for those in financial distress

Not everyone could participate. If you were a self-employed professional, a domestic worker or a field hand, you were not eligible. Neither were government employees, nor many teachers, nurses, hospital employees, librarians and social workers. Social Security was not originally intended to be a permanent program, but eventually it was expanded, and it became a permanent part of our society.

Many amendments have been passed since 1935 that extended eligibility to survivors and dependents of retired workers, domestic and farm workers, non-farm self-employed professionals and some federal workers, as well as some people in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Benefits were increased, and the Social Security Administration set a new contribution schedule.

In 1960, President Eisenhower added benefits for disabled workers and their dependents. In 1965, Medicare was added to Social Security beneficiaries 65 or older, who could also purchase supplemental insurance, and in 1972, President Nixon added an automatic cost of living increase to offset inflation.

By 1977, Social Security was in trouble. Amendments were passed to change the benefit qualification, increasing the payroll tax and decreasing benefits. In 1981, President Reagan created a commission to figure out how to keep the plan soluble, and beginning in 1983, the retirement age was gradually increased to 67, Social Security benefits were taxed, and benefits were given to federal workers.

President Bush expanded the Medicare prescription drug coverage, eliminated wage credits for military personnel and extended disability benefits and food stamps to qualified immigrants and their children.

President Obama temporarily reduced the Social Security tax rate from 6.2 to 4.2 for two years because of the Great Recession.

Every year, the Social Security Administration (SSA) makes changes to the program, such as cost of living (COL) adjustments, increases in taxable income, earnings limit increases and increases in disability changes, but no one has come up with a fix to keep the fund solvent. In 2015, Congress temporarily balanced the distribution of Social Security payroll contributions between Disability Insurance (DI) and the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI), which extended the solvency of the DI fund, which is projected to be able to pay full benefits until 2032.

How Does Social Security Work and Who Collects Benefits?

Workers and employers each pay 6.2% into the fund through the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA). 5.015% goes to the OASI trust fund and 1.185% goes into the DI trust fund. According to the National Academy of Social Insurance. Surpluses are invested in secure U.S. Treasury securities, which earn interest that goes to the trust funds.

As of 2018, more than 62 million people received Social Security, including retirees, survivors (widows, widowers, spouses and children) and the disabled, 3 in 10 of who are below 125% of the poverty line. Nearly 1 in 5 Americans receives benefits, and 1 in 4 families. 84% of everyone 65 and older receives Social Security; 61% of them get half or more of their income from Social Security and 33% get 90% or more.

What is the Current Problem?

Actuaries make assumptions based upon birth rates, death rates, immigration, employment, wages, inflation, productivity and interest rates and project estimates for the next 75 years. They predict, according to the National Academy of Social Insurance, that if action isn’t taken by the end of 2018, we will have to start drawing down on reserves. By 2034, these reserves will be depleted, and income will only cover 79% of benefits due then. By 2095, assuming no changes in taxes, benefits or assumptions, revenue would cover only about 75% of benefits due that year.

Why is this happening? Baby boomers are reaching age 65 and people are living longer after age 65. While birth rates are predicted to remain at replacement levels, people 65 and older will increase from 15% to 23% by 2095. Taxable income is due to drop 1.4% by 2095.

The National Academy of Social Insurance conducted a multigenerational study in 2014 and found that:

- Most Americans thought that benefits were too low.

- 77% said that preserving benefits, even if it means raising taxes on working Americans, is critical.

- 71% would prefer eliminating the taxable earnings cap, raising the tax rate by 1/20 of 1% per year, increasing the special minimum benefit and basing COLAs on inflation experienced by the elderly.

There have been proposals to improve the adequacy of benefits including: updating the special minimum benefit to keep long-serving, low-paid workers out of poverty when they retire, increasing benefits for the surviving spouse, reinstating benefits until age 22 for children of deceased or disabled workers, allowing 5 childcare years to count for credits, setting a minimum benefit for low-income couples and changing the benefit formula to increase benefits for all, but all this costs money.

What Fixes Have Been Proposed to Extend Solvency?

- Raising the retirement age, which will cut benefits across the board – increasing the age to 68 between 2023 and 2028 would reduce benefits by 7% and decrease the shortfall by 16%. Raising the retirement age to 70 between 2023 and 2069 would decrease benefits by 21% but would reduce the financing gap by 25%. 65% of people polled oppose increasing the age to age 68 and 75% oppose increasing it to age 70. The rationale behind raising the retirement age is that people are living longer and drawing benefits for longer, which was not contemplated back in 1935, when men expected to spend 13 years in retirement and women about 13 years. Republicans like this idea. Democrats have opposed this because it is a benefit cut no matter which way you look at it, and it disadvantages low income workers.

- Switching to the chained Consumer Price Index (CPI) for all urban consumers to the rate of inflation or rise of prices over time as the basis for Cost of Living increases – Republicans like this idea. Democrats argue that the current COLA doesn’t keep up with the inflation that seniors face because of higher out-of-pocket health care expenses that are rising faster than inflation, but they are generally in favor of this, as well as increasing payouts to those who have been receiving them for at least 20 years. 76% of people polled oppose it.

- Lifting the $128,400 cap on earnings on which workers and employers contribute to Social Security – if it were increased over the next 5 years to $230,000, it would reduce the shortfall by 29%, according to the National Academy of Social Insurance (NASI). If it were eliminated in 10 years, it would reduce 74% of the shortfall. This is supported by 80% of Americans polled. Only a small percentage of people earn that much a year (around 6%), so it makes sense for them to pay more. On the other hand, it would hurt self-employed and small business owners, discourage people from working more and it isn’t fair to the wealthy because they won’t see any increase in benefits even if they pay more. Democrats are in favor of doing this.

- Means testing those who receive benefits – it would reduce or eliminate benefits for individuals with incomes over $110,000 and couples over $165,000. This would reduce the shortfall by 20%. 60% of those polled are against this (64% of Republicans, 60% of Democrats and 56% of Independents). Those against this idea say that the income guidelines hardly make them “high earners”, and that with rising health costs, depending on home equity, pensions and savings can be iffy when some economists are predicting another recession while we are still recovering from the last one. It would also change Social Security from an earned right to welfare, and the government would have to constantly check your income and assets to adjust your benefit.

- Gradually increasing the contribution rate (currently 6.2%) -if it were increased to 7.2% over 20 years, it would reduce the Social Security funding shortfall by 52%. 83% of those polled support this change. Increasing it to 7.2% in 2023 and to 8.2% in 2052 would reduce the funding gap by 76%. This would cost around $9.60 a week for someone earning $50,000. 66% of those polled would be in favor of this idea, but it is a tax and would raise labor costs, while discouraging hiring and keeping jobs here in America. It would also hurt younger, older and low-wage earners.

- Subjecting 401(k)s and other salary reduction plans to Social Security contributions – Congress launched this reform in 1983, but they could add other salary reduction plans. The downside of this proposal is that it would increase the cost of healthcare and other employee benefits.

- Partial or full privatization of the program has been proposed by several Republicans, whereby a small amount of benefits would be placed into a retirement account that could be invested as the individual sees fit. The downside to this proposal is that very few Americans have the financial background to make wise investment choices and they could end up worse off.

- Instituting a value-added tax on consumption instead of the payroll tax -this would mean adding an average of $3100 to the pockets of the average family and would boost GDP growth, but then Social Security would need a new funding source, since payroll taxes supply about 86.5% of its revenue. Plus, consumption varies depending on whether there is growth or a recession.

- Cutting everyone’s benefits immediately – this would fix the 75-year shortfall, but everyone would lose 21% of their monthly benefits.

- Restoring the estate tax to the 2000 level and dedicating those funds to Social Security or taxing the wealthy.

- Increasing the number of years used to calculate initial benefits – this would fill 11% of the solvency gap. Most people are living and working longer than in the past and this would encourage people to work longer. The downside is that it would reduce benefits for those who need them the most, such as women, lower-income, less-educated and minorities, as well as their dependents and survivors.

- Covering all newly hired state and local government workers – about 25% are not covered by Social Security, but by retirement plans. This could decrease the funding gap by 6% but eventually, these workers would have to be paid benefits. At one time, some would have said that government workers would be unlikely to give up their pensions but considering the problems that there have been with some pension funds going bankrupt and being mismanaged, some might be willing to switch to something that is a better bet.

- Doing nothing and raising taxes and/or cutting benefits in 2034 – it is unlikely that anyone in Congress will agree to this.

Is There a Solution?

Some combination of a modest increase in the retirement age to 68, switching to the chained CPI, lifting the $128,400 cap, means testing, a small increase in the number of years used to calculate initial benefits and increasing the contribution rate to 7.2% is the most likely formula to get bi-partisan congressional, as well as public support. If we don’t suffer another major recession, which would affect the amount of money coming into the fund, this keep the fund solvent until 2095. If the economy grows faster, it could last longer.

It is in the interest of both parties to come up with a solution, and now that there is a new Democratic majority in the House of Representatives, while Republicans control the Senate, Republicans will have to reach across the aisle to their Democratic colleagues if they want to find a solution for the shortfall. This is going to be difficult, as most of the moderate Republicans in the House were defeated by Democrats, and the ones who are left may be less likely to want to work with them. We will be dipping into reserves by the end of this year, but whether either party will express any sense of urgency in coming up with a solution until they sort out how, or even if, they are going to agree to work together in the new Congress is doubtful.