Find a retiree who will tell you their monthly benefit is adequate.

Go ahead. We dare you. But one thing we aren’t going to do in the meanwhile is hold our breath.

Whether you’re asking a well-off retiree or a retiree on a tight budget, finding one who will agree their benefits are comparable to their contributions would be equivalent to finding the Loch Ness Monster. Calling their existence “questionable” is generous.

To be sure, the benefits most people receive wouldn’t be enough alone to maintain their working lifestyle. For those subsisting almost entirely on Social Security and reflecting on an entire working life of payroll contributions, it almost certainly seems like you don’t get back what you pay in.

But how many of us actually dig into the numbers to see if that’s true? Probably not many. A day of trying to make sure everything is paid on a modest Social Security check doesn’t really put one in the mood to stare at a bunch of numbers.

So, we’ll do that for you. Because although we know back in the day Social Security paid exponentially more to beneficiaries than they contributed, we aren’t entirely sure what those numbers look like in the new millennium ourselves.

Buckle up. This one’s gonna get complicated.

Claim: Social Security beneficiaries contributed more through payroll taxes than they receive in Social Security benefits.

To explore the truth behind this claim, we’re turning to the Urban Institute, a non-partisan research group whose staff of 550 mathematicians, demographers, economists, and social and data scientists explore the financial and demographic realities of Social Security each year.

Among other issues related to Social Security, the Urban Institute has published statistics about how much groups turning 65 in different years have contributed to Social Security versus how much they’ve collected in benefits. And since marital status can dramatically affect benefit amounts, each group was estimated using single filer and joint filer models.

Here is the Urban Institute’s complete report if you’d like to see all of the estimates throughout the years and how the organization arrived at them:

412660-Social-Security-and-Medicare-Taxes-and-Benefits-Over-a-Lifetime-UpdateWhen examining the findings given in this report, it’s important to note two things:

- Since the dollar has changed so much in value between 1960 and 2021, for the sake of understanding the real relationship between contributions and benefits throughout the decades, all amounts given in this report are converted to 2012 dollars (the time at which this report was published).

- This report is giving contribution and benefit amounts for both Social Security AND Medicare. So when it talks about “total lifetime taxes” and “total lifetime benefits,” it’s talking about the combined taxes and benefits for both programs.

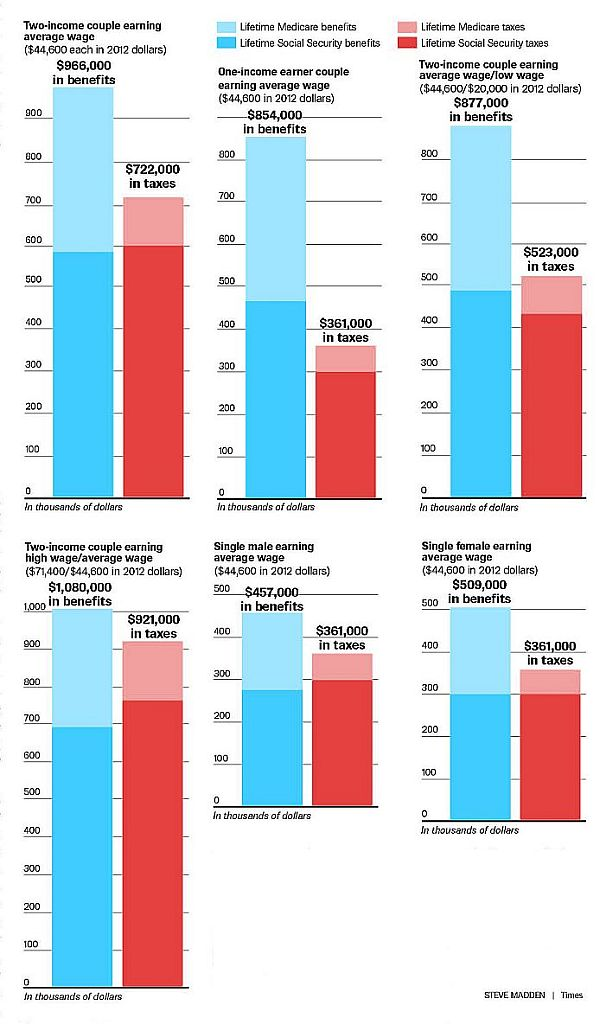

For now, let’s just look at one recent year of contribution and benefit amounts for six types of filers:

These are six types of filers who turned 65 in 2010 (there’s a reason why we’re looking at 2010, specifically, but we’ll get to that).

In all filing groups, retirees making the average United States salary were projected to collect significantly more in benefits than they contributed over their working history, with single-earner couples collecting the most benefits in relation to their contributions.

Looking through all the years given in the report—1960-2030—this ratio between contributions and benefits holds true. It would appear that at least since 1960, Social Security beneficiaries across filing groups are doing very well. Even single males, the group projected to receive the least benefits in relation to their contributions as of 2010, are projected to receive over $90,000 more in benefits than their lifetime contributions.

…Now let’s talk about why we’re so focused on 2010 out of all the years listed in the report.

The devil’s in the details:

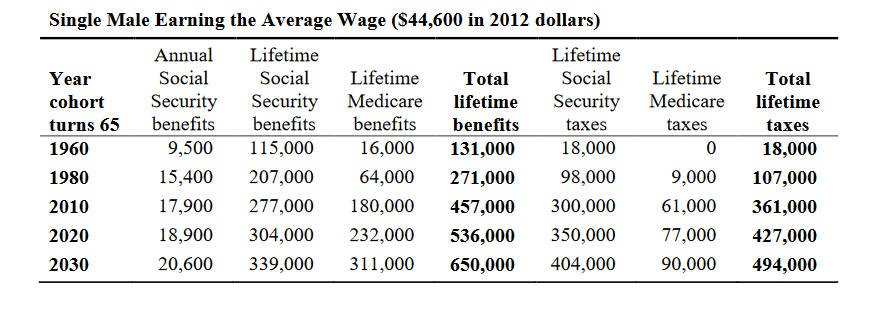

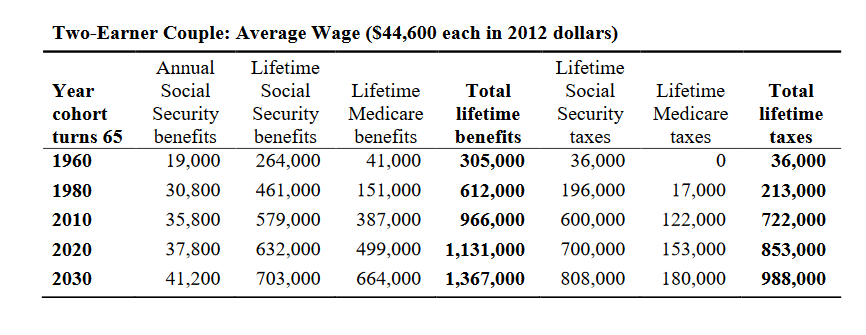

Here are two different groups of beneficiaries: single male filers and joint average wage filers, respectively.

In these tables you can see how the contributions and benefits break out between Social Security and Medicare. Since we’re focused on Social Security benefits versus contributions, we’re going to ignore the Medicare totals for now.

In 2010, we start to see an interesting thing happen with these beneficiary groups when we focus solely on Social Security.

A single male making an average salary who retired at 65 in 2010 contributed $300,000 in lifetime Social Security taxes. But he is only expected to collect $277,000 in lifetime Social Security benefits.

A couple making average salaries who retire at 65 in 2010 contributed $600,00 in lifetime Social Security taxes. But they are only expected to collect $579,000 in lifetime Social Security benefits.

While other types of filers are still expected to collect benefits in excess of their contributions, these are the first two groups to be expected NOT to collect benefits equal to their contributions. Though the other types of filers start to close the gap between benefit and contribution amounts toward 2020 and 2030.

Prior to 2010, and especially going back to 1960, all beneficiary groups truly did collect much more in benefits than they contributed. Only recently has that story changed, and only for certain types of beneficiaries.

The argument we’ve seen made with regards to this report is it definitively puts to bed the idea that beneficiaries aren’t getting what they paid in. And if you look at the sum total of the information given, that would appear to be true.

…But it’s only true if you factor Medicare taxes and benefits into the equation.

Combined with the benefits retirees receive from Medicare, yes. Retirees receive far more in benefits than they contribute and are projected to continue doing so well into the future.

But if we are strictly talking about Social Security? That doesn’t seem to be the case for everyone. The data shows that as of 2021, at least three different types of beneficiaries are NOT expected to get back everything they put in.

So, this one is a little bit of a mixed bag. If you retired long before 2010, chances are good you’ll get back what you put in and then some. More recent retirees or those who have yet to turn 65 or retire, however, may not be able to say the same.

So our verdict on whether or not this claim is true is: kinda. The majority of those making the claim are likely incorrect, but it’s not true to say ALL retirees are incorrect in saying it.