About two years ago for several weeks, we heard this question non-stop: how can Social Security run out of money when the Treasury can just print more?

At that time there was an explosion of interest in Modern Monetary Theory (sometimes called Modern Money Theory), a macroeconomic theory questioning the legitimacy of “federal debt” and the existence of unemployment.

MMT, in the most general explanation, is a belief that a government that issues its own fiat currency can’t actually ever be in debt.

Essentially, if you are the sole source and creator of your own money, there’s no limit to how much of your own money you can make. Therefore, you can always create money to pay for things you may need or debts you have. If you are infinitely able to print your own money, debt and the inability to pay that debt is entirely voluntary.

Under MMT, the only real limit to a government’s ability to print money is inflation. But the theory addresses inflation by asserting demand-pull inflation can be controlled by raising taxes and removing currency from the economy.

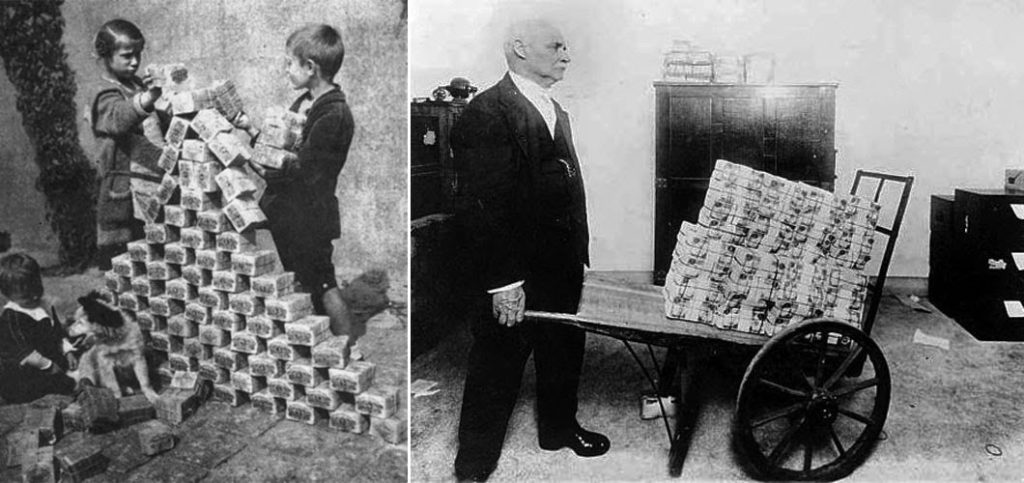

This is only a very simple explanation of the concept. Admittedly, we had to do some research when we first heard about it. And frankly, at the time, it was a concept we had trouble wrapping our heads around: “just print more money!” All we could think about are those famous pictures of people pushing wheelbarrows full of hyperinflated Papiermarks down the street during the Weimar Republic.

But this isn’t a discussion about endorsing or refuting MMT—and it’s definitely not a recap of post-war German economic history.

What we’re talking about today is strictly what prevents the federal government from simply “printing more money” to fill the gap in Social Security’s funding. Or more specifically, what prevents the Social Security Administration from calling up the Treasury to ask for more cash.

By now you probably know what’s happening to Social Security, but here’s a refresher just in case:

Over the years, we’ve had five workers contributing payroll taxes to the Trust Fund for every one retiree claiming Social Security benefits. But these days, there are only about two workers contributing for every one retiree’s benefits.

Back when we had a larger pool of workers contributing, Social Security took in an excess of contributions. That excess was invested in Treasury notes to be redeemed and paid in full to Social Security should there be any time when workers couldn’t contribute the amount needed to pay retirees’ full scheduled benefits.

This was done intentionally with the birth of what was then the largest generation ever: the Baby Boomers. We knew when this generation retired, we’d need additional money in the Trust to pay their benefits. And that’s where we’re at now.

The problem is despite today’s Millennial workers surpassing the Boomers in number, wages have been stagnant. And as we recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, we may come to find wages will be even more reluctant to rise if they don’t simply just slip lower.

We are now eating well into that surplus of funds. And with an even LARGER generation just behind them, demand on the Trust Fund will be higher than ever before in just about 30 years. There’s also the issue that birth rates for these new generations of workers are plummeting, suggesting we’ll have even MORE of a Social Security funding crisis in the future.

Our most immediate funding crisis is set to occur in 2034—in 13 years. That’s how long it will take until we’ve redeemed the last Treasury bill and soaked the last drop of our surplus. It’s also how long Congress has to come up with a workaround to avoid the mandatory 25% benefit cuts that will trigger the day we don’t have the money in reserves to pay current scheduled benefits.

As we said before, a lot of people think that’s preposterous. The government keeps money everywhere. It PRINTS the money. Why would benefit cuts be MANDATORY if we reach this situation? Why can’t the SSA get the government to just make more money and subsidize the program?

The answer is: it can’t. It would be illegal to do so.

Way back in 1884, the federal government ratified the Antideficiency Act. The Antideficiency Act is a law that expands on one of our oldest pieces of legislation, Article One of the United States Constitution.

Article One states, “No money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in consequence of appropriations made by law.” In other words, the government has “the power of the purse,” and therefore only it can decide to provide money to any person or thing.

Under the Antideficiency Act, it is further stated that no federal employee or bureau can pull money out of the Treasury beyond what has been specified by appropriations.

GAOREPORTS-GAO-OGC-92-13…Skip ahead to Chapter 6 if you want the official rundown of how the Antideficiency Act works.

As a side note, this law is actually why we have so many federal government shutdowns. Because federal bureaus and programs can’t just take money out of the country’s wallet without permission from Mom and Dad (AKA Congress), when these bureaus reach the end of their appropriations money, they have to shut down until a new appropriations bill is decided.

So while the government MAY have the ability to print money at its leisure, and while Congress DOES have the ability to pass an emergency appropriations bill to rush funding from one place to another, the Social Security Administration doesn’t. And their appropriated funds aren’t anything that comes from the federal budget—it comes from U.S. taxpayers directly.

This means when Social Security exhausts its reserves, benefit cuts will indeed be mandatory. The SSA is prohibited from spending in excess of its appropriated funds.

And even if Congress were to step in and attempt to subsidize the funding gap? The founding principles and logic of Social Security would instantly evaporate. Social Security would no longer be a program for the people, funded directly by the people. It would partially become a federal welfare program for retirees that would immediately go on-budget as a traditional government expense instead of the off-budget self-funded program it is now.

Not only would this remove the sense of total ownership Social Security’s architects wanted beneficiaries to feel, but putting Social Security on-budget would almost instantly open it up to attack from lawmakers who lay awake at night sweating about the federal debt.

Realistically, it’s far more likely a bill would pass to assemble a team of scientists to find ways to resurrect dinosaurs than a bill to move general federal funds into Social Security for the unforeseeable future. We’re having a hard enough time as it is motivating them to do ANYTHING to avert the funding crisis as it is—and nobody has even tried to ask for general funds to do so.

So, if you’re one of the ones who has wondered why the SSA can’t just “get more money” out of the government’s massive piggy bank to continue paying full benefits past 2034, that’s why: that darned Antideficiency Act. The much more realistic fix will involve asking the same people who have provided the funds in the first place to make up the difference, via raising the retirement age and increasing payroll taxes either across the board or focusing on the wealthiest Americans who don’t currently contribute to payroll taxes on all of their income.